Отладка #

Отладка WebRTC может быть сложной задачей. Существует много подвижных частей, и они могут ломаться независимо. Если вы не будете осторожны, вы можете потерять недели, глядя не на те вещи. Когда вы наконец найдете сломанную часть, вам придется кое-что изучить, чтобы понять почему.

Эта глава поможет вам настроиться на отладку WebRTC. Она покажет, как разбить проблему на составляющие. После того, как мы поймем проблему, мы быстро обзорно рассмотрим популярные инструменты отладки.

Изолируйте проблему #

При отладке вам нужно изолировать источник проблемы. Начните с самого начала…

Проверка STUN-сервера с помощью netcat: #

Подготовьте 20-байтный пакет binding-запроса:

00 01 00 00 21 12 a4 42 54 45 53 54 54 45 53 54 54 45 53 54Интерпретация:

00 01- тип сообщения.00 00- длина раздела данных.21 12 a4 42- магический cookie.54 45 53 54 54 45 53 54 54 45 53 54(декодируется в ASCII какTESTTESTTEST) - 12-байтный идентификатор транзакции.

Отправьте запрос и ждите 32-байтный ответ:

echo -ne '\x00\x01\x00\x00\x21\x12\xa4\x42\x54\x45\x53\x54\x54\x45\x53\x54\x54\x45\x53\x54' | nc -u stun.l.google.com 19302 | xxdИнтерпретация:

01 01- тип сообщения00 0c- длина раздела данных, декодируется в 12 в десятичной системе21 12 a4 42- магический cookie54 45 53 54 54 45 53 54 54 45 53 54(декодируется в ASCII какTESTTESTTEST) - 12-байтный идентификатор транзакции.00 20 00 08 00 01 6f 32 7f 36 de 89- 12-байтные данные, интерпретация:00 20- тип:XOR-MAPPED-ADDRESS00 08- длина раздела значений, декодируется в 8 в десятичной системе00 01 6f 32 7f 36 de 89- значение данных, интерпретация:00 01- тип адреса (IPv4)6f 32- XOR-mapped порт7f 36 de 89- XOR-mapped IP-адрес

Декодирование XOR-mapped раздела громоздко, но мы можем заставить STUN-сервер выполнить фиктивное XOR-маскирование, предоставив (недопустимый) фиктивный магический cookie, установленный в 00 00 00 00:

echo -ne '\x00\x01\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x54\x45\x53\x54\x54\x45\x53\x54\x54\x45\x53\x54' | nc -u stun.l.google.com 19302 | xxd

XOR с фиктивным магическим cookie идемпотентен, поэтому порт и адрес будут в открытом виде в ответе. Это не сработает во всех ситуациях, потому что некоторые маршрутизаторы манипулируют проходящими пакетами, жульничая с IP-адресом. Если мы посмотрим на возвращаемое значение данных (последние восемь байт):

00 01 4e 20 5e 24 7a cb- значение данных, интерпретация:00 01- тип адреса (IPv4)4e 20- mapped порт, который декодируется в 20000 в десятичной системе5e 24 7a cb- IP-адрес, который декодируется в94.36.122.203в точечно-десятичной нотации.

Сбой безопасности #

Сбой медиа #

Сбой данных #

Инструменты профессионала #

netcat (nc) #

netcat - это утилита командной строки для чтения и записи сетевых подключений с использованием TCP или UDP. Обычно доступна как команда nc.

tcpdump #

tcpdump - анализатор сетевых пакетов из командной строки.

Распространенные команды:

Захватить UDP-пакеты к и от порта 19302, вывести шестнадцатеричный дамп содержимого пакета:

sudo tcpdump 'udp port 19302' -xxТо же самое, но сохранить пакеты в файл PCAP (packet capture) для последующего осмотра:

sudo tcpdump 'udp port 19302' -w stun.pcapФайл PCAP можно открыть в приложении Wireshark:

wireshark stun.pcap

Wireshark #

Wireshark - широко используемый анализатор сетевых протоколов.

Инструменты WebRTC в браузерах #

Браузеры имеют встроенные инструменты, которые можно использовать для проверки устанавливаемых подключений. Chrome имеет chrome://webrtc-internals и chrome://webrtc-logs. Firefox имеет about:webrtc.

Задержка #

Задержка от конца до конца не является простой суммой задержек каждого компонента.

Хотя теоретически можно измерить задержку компонентов конвейера передачи живого видео по отдельности, а затем сложить их, на практике по крайней мере некоторые компоненты будут либо недоступны для инструментирования, либо будут давать значительно отличающиеся результаты при измерении вне конвейера. Переменные глубины очередей между этапами конвейера, топология сети и изменения экспозиции камеры - лишь несколько примеров компонентов, влияющих на задержку от конца до конца.

Внутренняя задержка каждого компонента в системе потоковой передачи может меняться и влиять на последующие компоненты. Даже содержимое захваченного видео влияет на задержку. Например, для высокочастотных элементов, таких как ветви деревьев, требуется гораздо больше битов по сравнению с низкочастотным чистым голубым небом. Камера с включенной автоэкспозицией может захватывать кадр гораздо дольше ожидаемых 33 миллисекунд, даже если частота съемки установлена на 30 кадров в секунду. Передача по сети, особенно сотовой, также очень динамична из-за меняющегося спроса. Больше пользователей означает больше трафика в эфире. Ваше физическое местоположение (известные зоны слабого сигнала) и множество других факторов увеличивают потери пакетов и задержку.

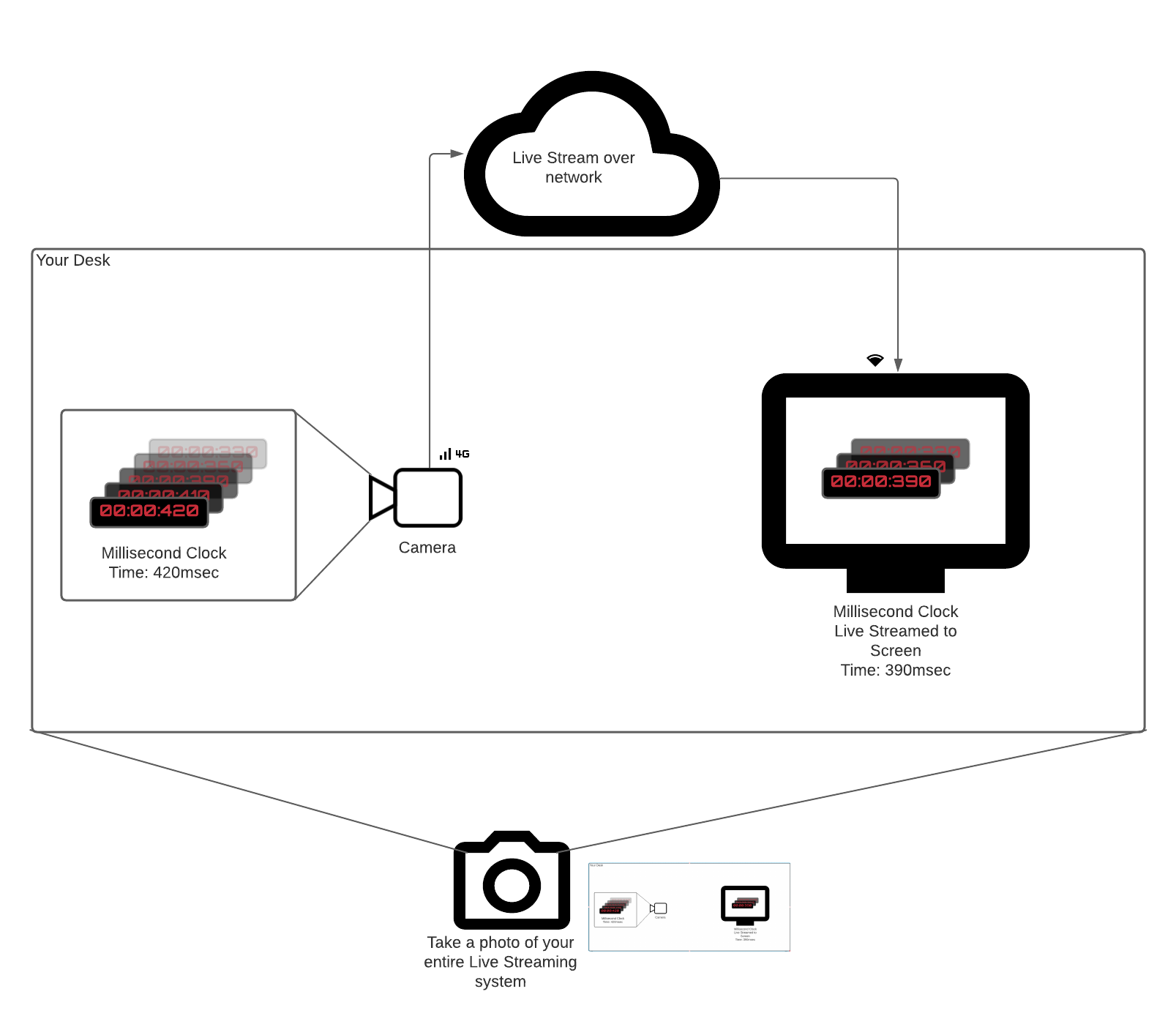

Ручное измерение задержки от конца до конца #

Когда мы говорим о задержке от конца до конца, мы подразумеваем время между происходящим событием и его наблюдением, то есть появлением видеокадров на экране.

EndToEndLatency = T(observe) - T(happen)

Наивный подход - зафиксировать время происходящего события и вычесть из времени наблюдения. Однако при уточнении до миллисекунд синхронизация времени становится проблемой. Попытки синхронизировать часы в распределенных системах в основном бесполезны, даже небольшая ошибка синхронизации времени приводит к недостоверному измерению задержки.

Простой обходной путь для проблем синхронизации часов - использовать один и тот же clock. Поместите отправителя и получателя в одну систему отсчета.

Представьте, что у вас есть тикающие миллисекундные часы или любой другой источник событий. Вы хотите измерить задержку в системе, которая транслирует часы на удаленный экран, наведя на них камеру. Очевидный способ измерить время между тиканием миллисекундного таймера (Thappen) и появлением видеокадров часов на экране (Tobserve) следующий:

- Наведите камеру на миллисекундные часы.

- Отправьте видеокадры получателю, находящемуся в том же физическом месте.

- Сфотографируйте (используйте телефон) миллисекундный таймер и полученное видео на экране.

- Вычтите два времени.

Это самое правдивое измерение задержки от конца до конца. Оно учитывает задержки всех компонентов (камера, кодировщик, сеть, декодер) и не полагается на синхронизацию часов.

.

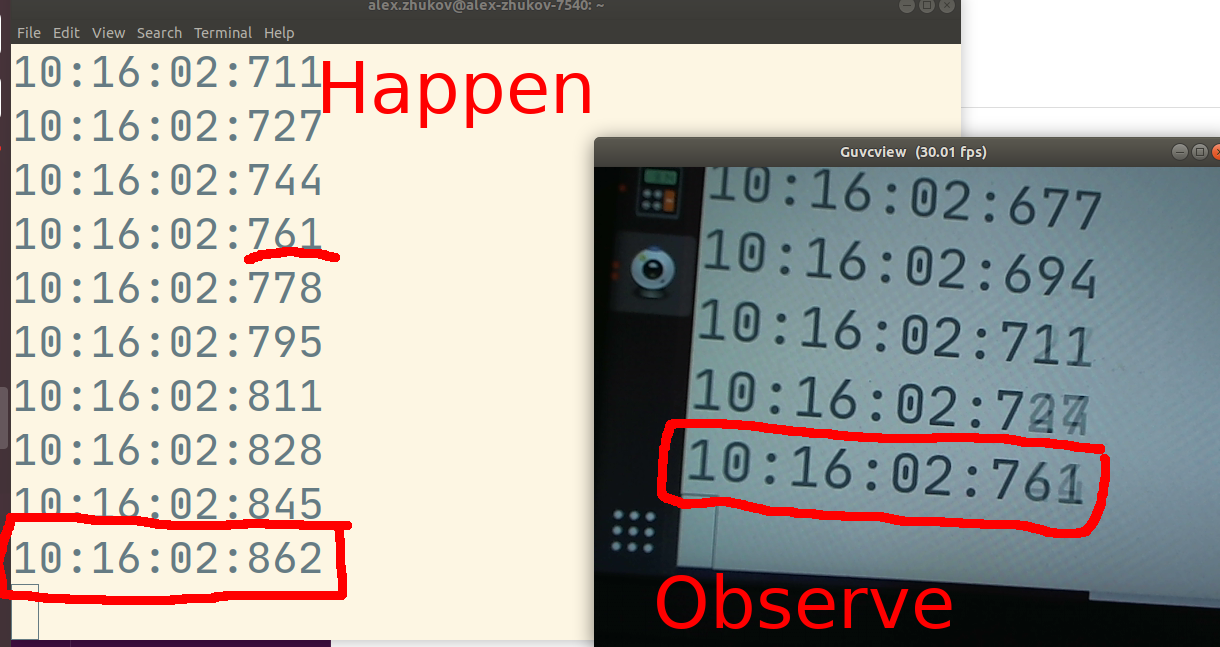

.

На фото выше измеренная задержка от конца до конца составляет 101 мс. Событие происходит прямо сейчас в 10:16:02.862, но наблюдатель системы потоковой передачи видит 10:16:02.761.

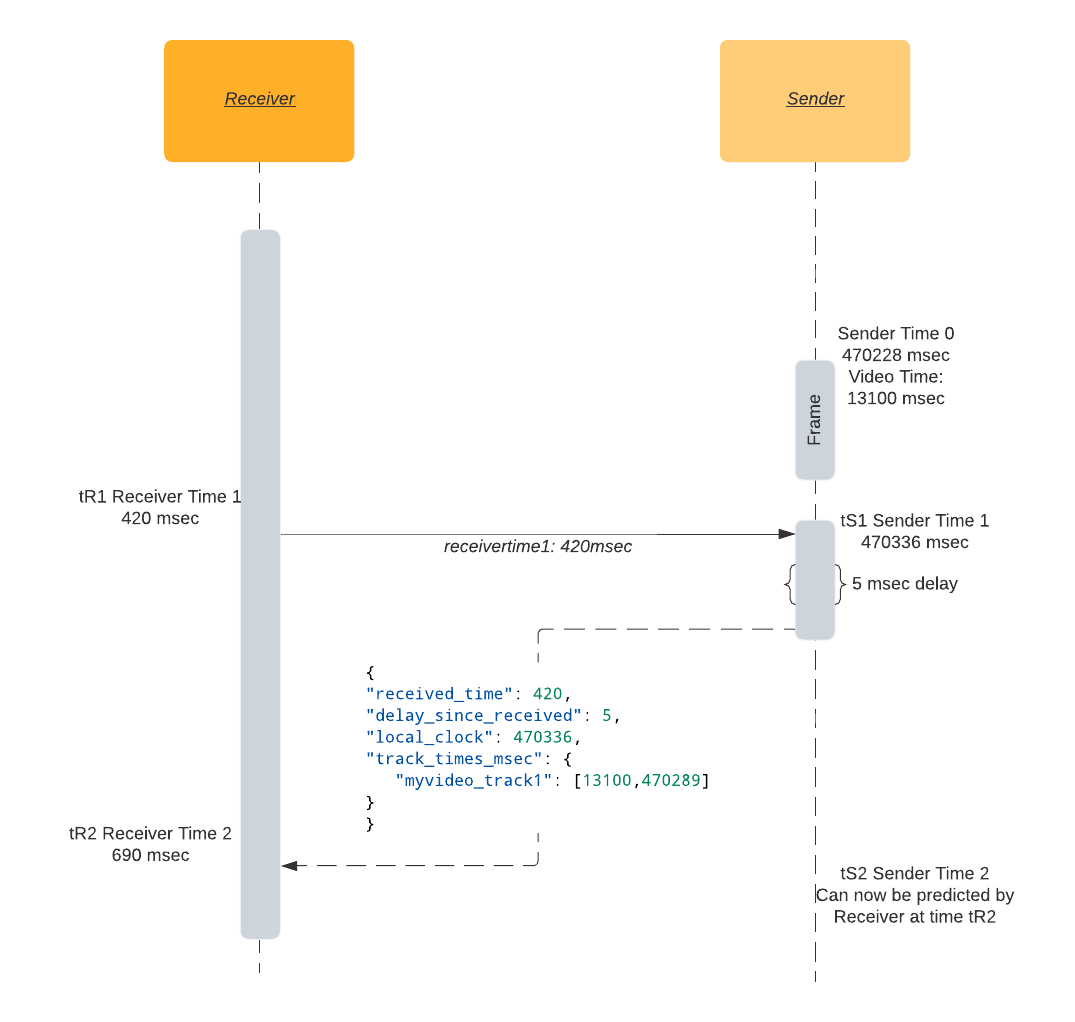

Автоматическое измерение задержки от конца до конца #

На момент написания (май 2021 года) стандарт WebRTC для задержки от конца до конца активно обсуждается. Firefox реализовал набор API для создания автоматических измерений задержки поверх стандартных WebRTC API. Однако в этом параграфе мы обсудим наиболее совместимый способ автоматического измерения задержки.

Время кругового обхода вкратце: я отправляю вам свое время tR1, когда я получаю обратно мой tR1 во время tR2, я знаю, что время кругового обхода равно tR2 - tR1.

При наличии канала связи между отправителем и получателем (например, DataChannel) получатель может смоделировать монотонные часы отправителя, выполнив следующие шаги:

- Во время

tR1получатель отправляет сообщение со своей локальной меткой времени монотонных часов. - Когда оно принимается отправителем с локальным временем

tS1, отправитель отвечает копиейtR1, а также своимtS1и временем видеодорожки отправителяtSV1. - Во время

tR2на стороне получателя время кругового обхода вычисляется путем вычитания времени отправки и получения сообщения:RTT = tR2 - tR1. - Время кругового обхода

RTTвместе с локальной меткой времени отправителяtS1достаточно для создания оценки монотонных часов отправителя. Текущее время на отправителе во времяtR2будет равноtS1плюс половина времени кругового обхода. - Локальная метка времени отправителя

tS1, сопоставленная с меткой времени видеодорожкиtSV1вместе со временем кругового обходаRTT, достаточна для синхронизации времени видеодорожки получателя со временем видеодорожки отправителя.

Теперь, когда мы знаем, сколько времени прошло с момента последнего известного времени видеокадра отправителя tSV1, мы можем приблизительно оценить задержку, вычтя время текущего отображаемого видеокадра (actual_video_time) из ожидаемого времени:

expected_video_time = tSV1 + time_since(tSV1)

latency = expected_video_time - actual_video_time

Недостаток этого метода заключается в том, что он не включает внутреннюю задержку камеры. Большинство видеосистем считают метку времени захвата кадра временем доставки кадра с камеры в основную память, что происходит через несколько мгновений после фактического происходящего события.

Пример оценки задержки #

Образец реализации открывает канал данных latency на получателе и периодически отправляет метки времени монотонного таймера получателя отправителю. Отправитель отвечает JSON-сообщением, и получатель вычисляет задержку на основе сообщения.

{

"received_time": 64714, // Метка времени, отправленная получателем, отражается отправителем.

"delay_since_received": 46, // Время, прошедшее с момента последнего полученного `received_time` на отправителе.

"local_clock": 1597366470336, // Текущее время монотонных часов отправителя.

"track_times_msec": {

"myvideo_track1": [

13100, // Метка времени RTP видеокадра (в миллисекундах).

1597366470289 // Метка времени монотонных часов видеокадра.

]

}

}

Откройте канал данных на получателе:

dataChannel = peerConnection.createDataChannel('latency');

Отправляйте время получателя tR1 периодически. В этом примере используется 2 секунды без особой причины:

setInterval(() => {

let tR1 = Math.trunc(performance.now());

dataChannel.send("" + tR1);

}, 2000);

Обработайте входящее сообщение от получателя на отправителе:

// Предполагаем, что event.data - строка вида "1234567".

tR1 = event.data

now = Math.trunc(performance.now());

tSV1 = 42000; // Текущая метка времени RTP кадра, преобразованная в миллисекундный масштаб.

tS1 = 1597366470289; // Текущая метка времени монотонных часов кадра.

msg = {

"received_time": tR1,

"delay_since_received": 0,

"local_clock": now,

"track_times_msec": {

"myvideo_track1": [tSV1, tS1]

}

}

dataChannel.send(JSON.stringify(msg));

Обработайте входящее сообщение от отправителя и выведите оценку задержки в console:

let tR2 = performance.now();

let fromSender = JSON.parse(event.data);

let tR1 = fromSender['received_time'];

let delay = fromSender['delay_since_received']; // Сколько времени прошло между получением и отправкой ответа отправителем.

let senderTimeFromResponse = fromSender['local_clock'];

let rtt = tR2 - delay - tR1;

let networkLatency = rtt / 2;

let senderTime = (senderTimeFromResponse + delay + networkLatency);

VIDEO.requestVideoFrameCallback((now, framemeta) => {

// Оценить текущее время отправителя.

let delaySinceVideoCallbackRequested = now - tR2;

senderTime += delaySinceVideoCallbackRequested;

let [tSV1, tS1] = Object.entries(fromSender['track_times_msec'])[0][1]

let timeSinceLastKnownFrame = senderTime - tS1;

let expectedVideoTimeMsec = tSV1 + timeSinceLastKnownFrame;

let actualVideoTimeMsec = Math.trunc(framemeta.rtpTimestamp / 90); // Преобразование базы времени RTP (90000) в миллисекундную базу.

let latency = expectedVideoTimeMsec - actualVideoTimeMsec;

console.log('latency', latency, 'msec');

});

Фактическое время видео в браузере #

<video>.requestVideoFrameCallback()позволяет веб-авторам получать уведомления о представлении кадра для компоновки.

До недавнего времени (до мая 2020 года) было практически невозможно надежно получить метку времени текущего отображаемого видеокадра в браузерах. Существовали обходные методы на основе video.currentTime, но они были не особенно точными.

Разработчики браузеров Chrome и Mozilla поддержали введение нового стандарта W3C, HTMLVideoElement.requestVideoFrameCallback(), который добавляет API-обратный вызов для доступа к текущему времени видеокадра.

Хотя дополнение кажется тривиальным, оно позволило создать множество сложных медиаприложений в Интернете, требующих синхронизации аудио и видео.

Специально для WebRTC обратный вызов будет включать поле rtpTimestamp, метку времени RTP, связанную с текущим видеокадром. Это должно быть присутствующим для приложений WebRTC, но отсутствовать в других случаях.

Советы по отладке задержки #

Поскольку отладка, вероятно, повлияет на измеряемую задержку, общее правило - упростить вашу настройку до наименьшего возможного размера, который все еще может воспроизвести проблему. Чем больше компонентов вы сможете удалить, тем легче будет определить, какой компонент вызывает проблему с задержкой.

Задержка камеры #

В зависимости от настроек камеры ее задержка может варьироваться. Проверьте настройки автоэкспозиции, автофокуса и автоматического баланса белого. Все “автоматические” функции веб-камер занимают дополнительное время для анализа захваченного изображения перед его передачей в стек WebRTC.

Если вы используете Linux, вы можете использовать инструмент командной строки v4l2-ctl для управления настройками камеры:

# Отключить автофокус:

v4l2-ctl -d /dev/video0 -c focus_auto=0

# Установить фокус на бесконечность:

v4l2-ctl -d /dev/video0 -c focus_absolute=0

Вы также можете использовать графический инструмент guvcview для быстрой проверки и настройки параметров камеры.

Задержка кодировщика #

Большинство современных кодировщиков будут буферизовать некоторые кадры перед выводом закодированного. Их первый приоритет - баланс между качеством создаваемой картинки и битрейтом. Многопроходное кодирование - крайний пример пренебрежения кодировщика к выходной задержке. Во время первого прохода кодировщик полностью поглощает все видео и только после этого начинает выводить кадры.

Однако с правильной настройкой люди достигали субкадровых задержек. Убедитесь, что ваш кодировщик не использует чрезмерное количество эталонных кадров и не полагается на B-кадры. Настройки задержки каждого кодека различаются, но для x264 мы рекомендуем использовать tune=zerolatency и profile=baseline для минимальной задержки вывода кадров.

Сетевая задержка #

Сетевой задержкой вы можете arguably сделать меньше всего, кроме как обновить сетевое подключение. Сетевая задержка очень похожа на погоду - вы не можете остановить дождь, но можете посмотреть прогноз и взять зонт. WebRTC измеряет сетевые условия с точностью до миллисекунд.

Важные метрики:

- Время кругового обхода.

- Потеря пакетов и повторные передачи пакетов.

Время кругового обхода

Стек WebRTC имеет встроенный механизм измерения времени кругового обхода сети (RTT) механизм. Достаточно хорошее приближение задержки - половина RTT. Предполагается, что отправка и получение пакета занимают одинаковое время, что не всегда так. RTT устанавливает нижнюю границу задержки от конца до конца. Ваши видеокадры не могут достичь получателя быстрее, чем RTT/2, независимо от того, насколько оптимизирован ваш конвейер от камеры до кодировщика.

Встроенный механизм RTT основан на специальных RTCP-пакетах, называемых отчетами отправителя/получателя. Отправитель отправляет свое показание времени получателю, получатель в свою очередь отражает тот же временной штамп обратно отправителю. Таким образом, отправитель знает, сколько времени заняла передача пакета получателю и обратно. Обратитесь к главе Отчеты отправителя/получателя для более подробной информации об измерении RTT.

Потеря пакетов и повторные передачи

Как RTP, так и RTCP - это протоколы на основе UDP, которые не гарантируют упорядочивания, успешной доставки или отсутствия дублирования. Все вышеперечисленное может и происходит в реальных приложениях WebRTC.

Несложная реализация декодера ожидает, что все пакеты кадра будут доставлены, чтобы декодер мог успешно восстановить изображение. При наличии потери пакетов могут появиться артефакты декодирования, если теряются пакеты P-кадра. Если теряются пакеты I-кадра, то все зависимые кадры либо получат серьезные артефакты, либо вообще не будут декодированы. Скорее всего, это приведет к “замораживанию” видео на мгновение.

Чтобы избежать (точнее, попытаться избежать) замораживания видео или артефактов декодирования, WebRTC использует сообщения отрицательного подтверждения (NACK). Когда получатель не получает ожидаемый RTP-пакет, он возвращает сообщение NACK, чтобы сообщить отправителю отправить отсутствующий пакет снова. Получатель ждет повторной передачи пакета. Такие повторные передачи вызывают увеличение задержки. Количество отправленных и полученных пакетов NACK записывается во встроенных статистических полях WebRTC outbound stream nackCount и inbound stream nackCount.

Вы можете увидеть красивые графики входящего и исходящего nackCount на странице внутренних данных WebRTC. Если вы видите, что nackCount увеличивается, это означает, что сеть испытывает высокую потерю пакетов, и стек WebRTC делает все возможное, чтобы создать гладкое видео/аудио-взаимодействие, несмотря на это.

Когда потеря пакетов настолько высока, что декодер не может создать изображение, или последующие зависимые изображения, как в случае полностью потерянного I-кадра, все будущие P-кадры не будут декодированы. Получатель попытается смягчить это, отправив специальное сообщение Picture Loss Indication (PLI). Как только отправитель получает PLI, он создаст новый I-кадр, чтобы помочь декодеру получателя. I-кадры обычно больше по размеру, чем P-кадры. Это увеличивает количество пакетов, которые необходимо передать. Как и с сообщениями NACK, получателю придется ждать нового I-кадра, что введет дополнительную задержку.

Следите за pliCount на странице внутренних данных WebRTC. Если он увеличивается, настройте кодировщик для создания меньшего количества пакетов или включите более устойчивый к ошибкам режим.

Задержка на стороне получателя #

Задержка будет зависеть от пакетов, приходящих не по порядку. Если нижняя часть пакета изображения придет раньше верхней, вам придется ждать верхнюю часть перед декодированием. Это подробно объясняется в главе Решение джиттера.

Вы также можете обратиться к встроенной метрике jitterBufferDelay, чтобы увидеть, как долго кадр удерживался в приемном буфере в ожидании всех его пакетов, прежде чем был передан декодеру.