Real-time Networking #

Why is networking so important in Real-time communication? #

Networks are the limiting factor in Real-time communication. In an ideal world we would have unlimited bandwidth and packets would arrive instantaneously. This isn’t the case though. Networks are limited, and the conditions could change at anytime. Measuring and observing network conditions is also a difficult problem. You can get different behaviors depending on hardware, software and the configuration of it.

Real-time communication also poses a problem that doesn’t exist in most other domains. For a web developer it isn’t fatal if your website is slower on some networks. As long as all the data arrives, users are happy. With WebRTC, if your data is late it is useless. No one cares about what was said in a conference call 5 seconds ago. So when developing a realtime communication system, you have to make a trade-off. What is my time limit, and how much data can I send?

This chapter covers the concepts that apply to both data and media communication. In later chapters we go beyond the theoretical and discuss how WebRTC’s media and data subsystems solve these problems.

What are the attributes of the network that make it difficult? #

Code that effectively works across all networks is complicated. You have lots of different factors, and they can all affect each other subtly. These are the most common issues that developers will encounter.

Bandwidth #

Bandwidth is the maximum rate of data that can be transferred across a given path. It is important to remember this isn’t a static number either. The bandwidth will change along the route as more (or less) people use it.

Transmission Time and Round Trip Time #

Transmission Time is how long it takes for a packet to arrive to its destination. Like Bandwidth this isn’t constant. The Transmission Time can fluctuate at anytime.

transmission_time = receive_time - send_time

To compute transmission time, you need clocks on sender and receiver synchronized with millisecond precision. Even a small deviation would produce an unreliable transmission time measurement. Since WebRTC is operating in highly heterogeneous environments, it is next to impossible to rely on perfect time synchronization between hosts.

Round-trip time measurement is a workaround for imperfect clock synchronization.

Instead of operating on distributed clocks a WebRTC peer sends a special packet with its own timestamp sendertime1.

A cooperating peer receives the packet and reflects the timestamp back to the sender.

Once the original sender gets the reflected time it subtracts the timestamp sendertime1 from the current time sendertime2.

This time delta is called “round-trip propagation delay” or more commonly round-trip time.

rtt = sendertime2 - sendertime1

Half of the round trip time is considered to be a good enough approximation of transmission time. This workaround is not without drawbacks. It makes the assumption that it takes an equal amount of time to send and receive packets. However on cellular networks, send and receive operations may not be time-symmetrical. You may have noticed that upload speeds on your phone are almost always lower than download speeds.

transmission_time = rtt/2

The technicalities of round-trip time measurement are described in greater detail in RTCP Sender and Receiver Reports chapter.

Jitter #

Jitter is the fact that Transmission Time may vary for each packet. Your packets could be delayed, but then arrive in bursts.

Packet Loss #

Packet Loss is when messages are lost in transmission. The loss could be steady, or it could come in spikes. This could be because of the network type like satellite or Wi-Fi. Or it could be introduced by the software along the way.

Maximum Transmission Unit #

Maximum Transmission Unit is the limit on how large a single packet can be. Networks don’t allow you to send one giant message. At the protocol level, messages might have to be split into multiple smaller packets.

The MTU will also differ depending on what network path you take. You can use a protocol like Path MTU Discovery to figure out the largest packet size you can send.

Congestion #

Congestion is when the limits of the network have been reached. This is usually because you have reached the peak bandwidth that the current route can handle. Or it could be operator imposed like hourly limits your ISP configures.

Congestion exhibits itself in many different ways. There is no standardized behavior. In most cases when congestion is reached the network will drop excess packets. In other cases the network will buffer. This will cause the Transmission Time for your packets to increase. You could also see more jitter as your network becomes congested. This is a rapidly changing area and new algorithms for congestion detection are still being written.

Dynamic #

Networks are incredibly dynamic and conditions can change rapidly. During a call you may send and receive hundreds of thousands of packets. Those packets will be traveling through multiple hops. Those hops will be shared by millions of other users. Even in your local network you could have HD movies being downloaded or maybe a device decides to download a software update.

Having a good call isn’t as simple as measuring your network on startup. You need to be constantly evaluating. You also need to handle all the different behaviors that come from a multitude of network hardware and software.

Solving Packet Loss #

Handling packet loss is the first problem to solve. There are multiple ways to solve it, each with their own benefits. It depends on what you are sending and how latency tolerant you are. It is also important to note that not all packet loss is fatal. Losing some video might not be a problem, the human eye might not even able to perceive it. Losing a users text messages are fatal.

Let’s say you send 10 packets, and packets 5 and 6 are lost. Here are the ways you can solve it.

Acknowledgments #

Acknowledgments is when the receiver notifies the sender of every packet they have received. The sender is aware of packet loss when it gets an acknowledgment

for a packet twice that isn’t final. When the sender gets an ACK for packet 4 twice, it knows that packet 5 has not been seen yet.

Selective Acknowledgments #

Selective Acknowledgments is an improvement upon Acknowledgments. A receiver can send a SACK that acknowledges multiple packets and notifies the sender of gaps.

Now the sender can get a SACK for packet 4 and 7. It then knows it needs to re-send packets 5 and 6.

Negative Acknowledgments #

Negative Acknowledgments solve the problem the opposite way. Instead of notifying the sender what it has received, the receiver notifies the sender what has been lost. In our case a NACK

will be sent for packets 5 and 6. The sender only knows packets the receiver wishes to have sent again.

Forward Error Correction #

Forward Error Correction fixes packet loss pre-emptively. The sender sends redundant data, meaning a lost packet doesn’t affect the final stream. One popular algorithm for this is Reed–Solomon error correction.

This reduces the latency/complexity of sending and handling Acknowledgments. Forward Error Correction is a waste of bandwidth if the network you are in has zero loss.

Solving Jitter #

Jitter is present in most networks. Even inside a LAN you have many devices sending data at fluctuating rates. You can easily observe jitter by pinging another device with the ping command and noticing the fluctuations in round-trip latency.

To solve jitter, clients use a JitterBuffer. The JitterBuffer ensures a steady delivery time of packets. The downside is that JitterBuffer adds some latency to packets that arrive early. The upside is that late packets don’t cause jitter. Imagine that during a call, you see the following packet arrival times:

* time=1.46 ms

* time=1.93 ms

* time=1.57 ms

* time=1.55 ms

* time=1.54 ms

* time=1.72 ms

* time=1.45 ms

* time=1.73 ms

* time=1.80 ms

In this case, around 1.8 ms would be a good choice. Packets that arrive late will use our window of latency. Packets that arrive early will be delayed a bit and can fill the window depleted by late packets. This means we no longer have stuttering and provide a smooth delivery rate for the client.

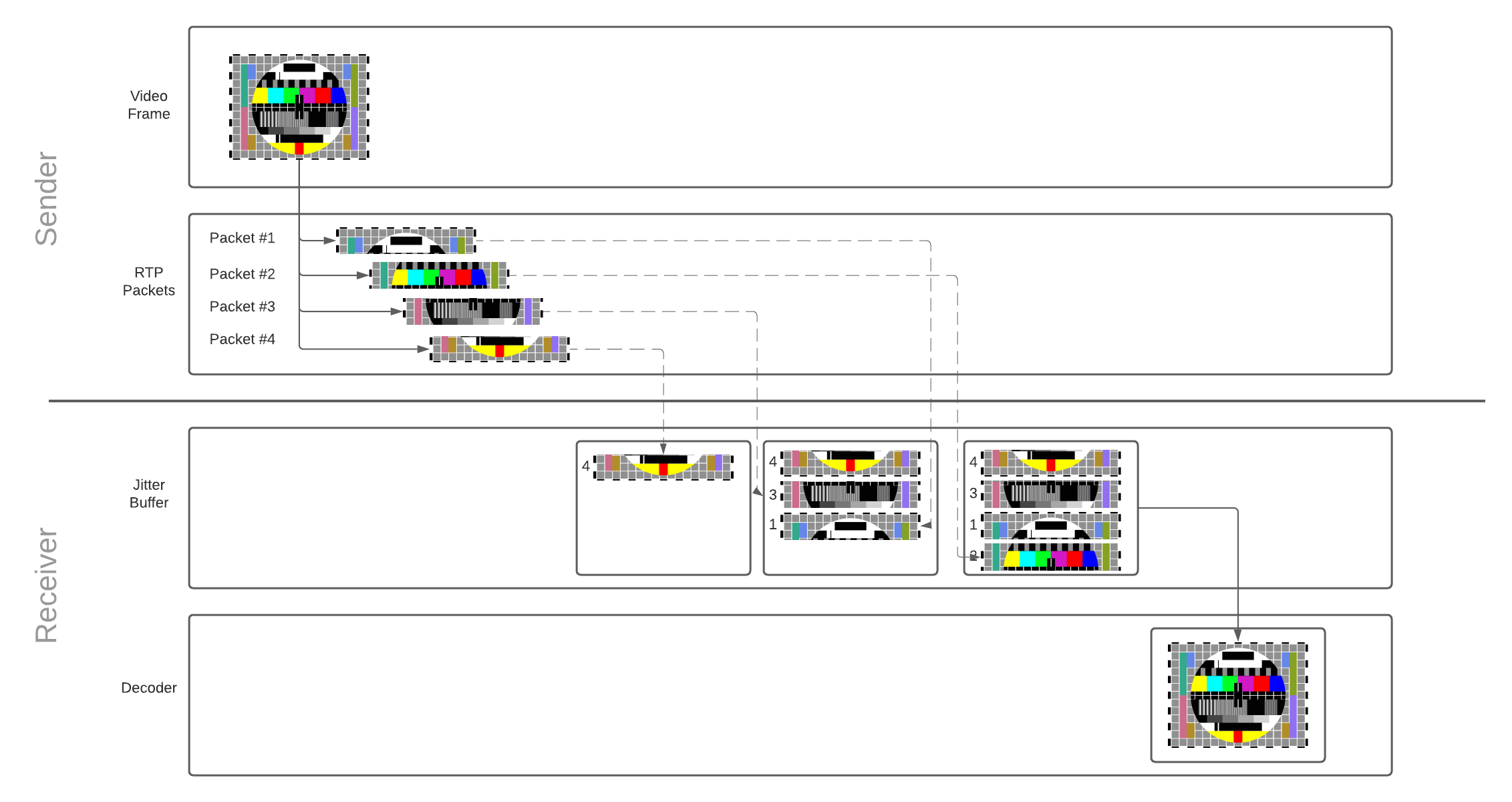

JitterBuffer operation #

Every packet gets added to the jitter buffer as soon as it is received. Once there are enough packets to reconstruct the frame, packets that make up the frame are released from the buffer and emitted for decoding. The decoder, in turn, decodes and draws the video frame on the user’s screen. Since the jitter buffer has a limited capacity, packets that stay in the buffer for too long will be discarded.

Read more on how video frames are converted to RTP packets, and why reconstruction is necessary in the media communication chapter.

jitterBufferDelay provides a great insight into your network performance and its influence on playback smoothness.

It is a part of WebRTC statistics API relevant to the receiver’s inbound stream.

The delay defines the amount of time video frames spend in the jitter buffer before being emitted for decoding.

A long jitter buffer delay means your network is highly congested.

Detecting Congestion #

Before we can even resolve congestion, we need to detect it. To detect it we use a congestion controller. This is a complicated subject, and is still rapidly changing. New algorithms are still being published and tested. At a high level they all operate the same. A congestion controller provides bandwidth estimates given some inputs. These are some possible inputs:

- Packet Loss - Packets are dropped as the network becomes congested.

- Jitter - As network equipment becomes more overloaded packets queuing will cause the times to be erratic.

- Round Trip Time - Packets take longer to arrive when congested. Unlike jitter, the Round Trip Time just keeps increasing.

- Explicit Congestion Notification - Newer networks may tag packets as at risk for being dropped to relieve congestion.

These values need to be measured continuously during the call. Utilization of the network may increase or decrease, so the available bandwidth could constantly be changing.

Resolving Congestion #

Now that we have an estimated bandwidth we need to adjust what we are sending. How we adjust depends on what kind of data we want to send.

Sending Slower #

Limiting the speed at which you send data is the first solution to preventing congestion. The Congestion Controller gives you an estimate, and it is the sender’s responsibility to rate limit.

This is the method used for most data communication. With protocols like TCP this is all done by the operating system and completely transparent to both users and developers.

Sending Less #

In some cases we can send less information to satisfy our limits. We also have hard deadlines on the arrival of our data, so we can’t send slower. These are the constraints that Real-time media falls under.

If we don’t have enough bandwidth available, we can lower the quality of video we send. This requires a tight feedback loop between your video encoder and congestion controller.