Media Communication #

What do I get from WebRTC’s media communication? #

WebRTC allows you to send and receive an unlimited amount of audio and video streams. You can add and remove these streams at anytime during a call. These streams could all be independent, or they could be bundled together! You could send a video feed of your desktop, and then include audio and video from your webcam.

The WebRTC protocol is codec agnostic. The underlying transport supports everything, even things that don’t exist yet! However, the WebRTC Agent you are communicating with may not have the necessary tools to accept it.

WebRTC is also designed to handle dynamic network conditions. During a call your bandwidth might increase, or decrease. Maybe you suddenly experience lots of packet loss. The protocol is designed to handle all of this. WebRTC responds to network conditions and tries to give you the best experience possible with the resources available.

How does it work? #

WebRTC uses two preexisting protocols RTP and RTCP, both defined in RFC 1889.

RTP (Real-time Transport Protocol) is the protocol that carries the media. It was designed to allow for real-time delivery of video. It does not stipulate any rules around latency or reliability, but gives you the tools to implement them. RTP gives you streams, so you can run multiple media feeds over one connection. It also gives you the timing and ordering information you need to feed a media pipeline.

RTCP (RTP Control Protocol) is the protocol that communicates metadata about the call. The format is very flexible and allows you to add any metadata you want. This is used to communicate statistics about the call. It is also used to handle packet loss and to implement congestion control. It gives you the bi-directional communication necessary to respond to changing network conditions.

Latency vs Quality #

Real-time media is about making trade-offs between latency and quality. The more latency you are willing to tolerate, the higher quality video you can expect.

Real World Limitations #

These constraints are all caused by the limitations of the real world. They are all characteristics of your network that you will need to overcome.

Video is Complex #

Transporting video isn’t easy. To store 30 minutes of uncompressed 720 8-bit video you need about 110 GB. With those numbers, a 4-person conference call isn’t going to happen. We need a way to make it smaller, and the answer is video compression. That doesn’t come without downsides though.

Video 101 #

We aren’t going to cover video compression in depth, but just enough to understand why RTP is designed the way it is. Video compression encodes video into a new format that requires fewer bits to represent the same video.

Lossy and Lossless compression #

You can encode video to be lossless (no information is lost) or lossy (information may be lost). Because lossless encoding requires more data to be sent to a peer, making for a higher latency stream and more dropped packets, RTP typically uses lossy compression even though the video quality won’t be as good.

Intra and Inter frame compression #

Video compression comes in two types. The first is intra-frame. Intra-frame compression reduces the bits used to describe a single video frame. The same techniques are used to compress still pictures, like the JPEG compression method.

The second type is inter-frame compression. Since video is made up of many pictures we look for ways to not send the same information twice.

Inter-frame types #

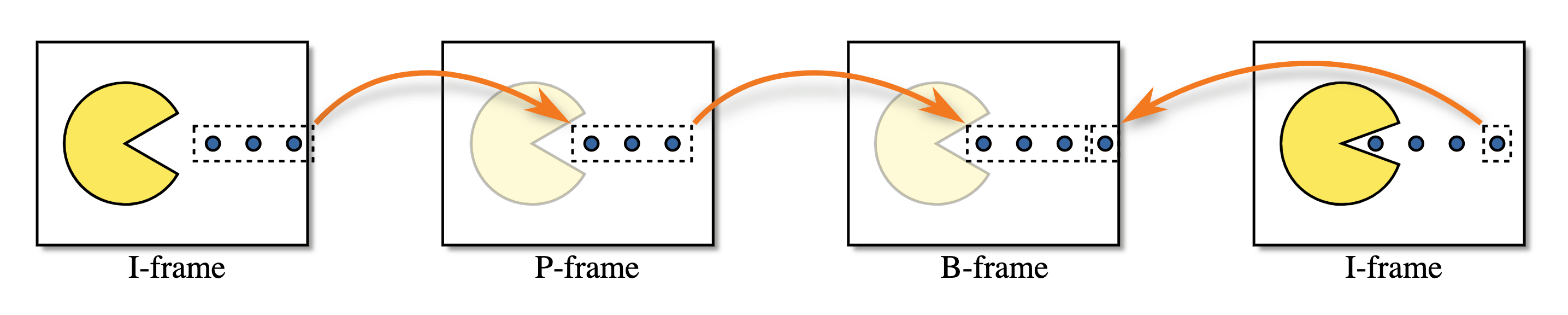

You then have three frame types:

- I-Frame - A complete picture, can be decoded without anything else.

- P-Frame - A partial picture, containing only changes from the previous picture.

- B-Frame - A partial picture, is a modification of previous and future pictures.

The following is visualization of the three frame types.

Video is delicate #

Video compression is incredibly stateful, making it difficult to transfer over the internet. What happens If you lose part of an I-Frame? How does a P-Frame know what to modify? As video compression gets more complex, this is becoming even more of a problem. Luckily RTP and RTCP have the solution.

RTP #

Packet Format #

Every RTP packet has the following structure:

0 1 2 3

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

|V=2|P|X| CC |M| PT | Sequence Number |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Timestamp |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Synchronization Source (SSRC) identifier |

+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+

| Contributing Source (CSRC) identifiers |

| .... |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Payload |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

Version (V) #

Version is always 2

Padding (P) #

Padding is a bool that controls if the payload has padding.

The last byte of the payload contains a count of how many padding bytes were added.

Extension (X) #

If set, the RTP header will have extensions. This is described in greater detail below.

CSRC count (CC) #

The amount of CSRC identifiers that follow after the SSRC, and before the payload.

Marker (M) #

The marker bit has no pre-set meaning, and can be used however the user likes.

In some cases it is set when a user is speaking. It is also commonly used to mark a keyframe.

Payload Type (PT) #

Payload Type is a unique identifier for what codec is being carried by this packet.

For WebRTC the Payload Type is dynamic. VP8 in one call may be different from another. The offerer in the call determines the mapping of Payload Types to codecs in the Session Description.

Sequence Number #

Sequence Number is used for ordering packets in a stream. Every time a packet is sent the Sequence Number is incremented by one.

RTP is designed to be useful over lossy networks. This gives the receiver a way to detect when packets have been lost.

Timestamp #

The sampling instant for this packet. This is not a global clock, but how much time has passed in the media stream. Several RTP packets can have the same timestamp if they for example are all part of the same video frame.

Synchronization Source (SSRC) #

An SSRC is the unique identifier for this stream. This allows you to run multiple streams of media over a single RTP stream.

Contributing Source (CSRC) #

A list that communicates what SSRCes contributed to this packet.

This is commonly used for talking indicators. Let’s say server side you combined multiple audio feeds into a single RTP stream. You could then use this field to say “Input stream A and C were talking at this moment”.

Payload #

The actual payload data. Might end with the count of how many padding bytes were added, if the padding flag is set.

Extensions #

RTCP #

Packet Format #

Every RTCP packet has the following structure:

0 1 2 3

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

|V=2|P| RC | PT | length |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Payload |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

Version (V) #

Version is always 2.

Padding (P) #

Padding is a bool that controls if the payload has padding.

The last byte of the payload contains a count of how many padding bytes were added.

Reception Report Count (RC) #

The number of reports in this packet. A single RTCP packet can contain multiple events.

Packet Type (PT) #

Unique Identifier for what type of RTCP Packet this is. A WebRTC Agent doesn’t need to support all these types, and support between Agents can be different. These are the ones you may commonly see though:

192- Full INTRA-frame Request (FIR)193- Negative ACKnowledgements (NACK)200- Sender Report201- Receiver Report205- Generic RTP Feedback206- Payload Specific Feedback

The significance of these packet types will be described in greater detail below.

Full INTRA-frame Request (FIR) and Picture Loss Indication (PLI) #

Both FIR and PLI messages serve a similar purpose. These messages request a full key frame from the sender.

PLI is used when partial frames were given to the decoder, but it was unable to decode them.

This could happen because you had lots of packet loss, or maybe the decoder crashed.

According to RFC 5104, FIR shall not be used when packets or frames are lost. That is PLIs job. FIR requests a key frame for reasons other than packet loss - for example when a new member enters a video conference. They need a full key frame to start decoding video stream, the decoder will be discarding frames until key frame arrives.

It is a good idea for a receiver to request a full key frame right after connecting, this minimizes the delay between connecting, and an image showing up on the user’s screen.

PLI packets are a part of Payload Specific Feedback messages.

In practice, software that is able to handle both PLI and FIR packets will act the same way in both cases. It will send a signal to the encoder to produce a new full key frame.

Negative Acknowledgment #

A NACK requests that a sender re-transmits a single RTP packet. This is usually caused by an RTP packet getting lost, but could also happen because it is late.

NACKs are much more bandwidth efficient than requesting that the whole frame get sent again. Since RTP breaks up packets into very small chunks, you are really just requesting one small missing piece. The receiver crafts an RTCP message with the SSRC and Sequence Number. If the sender does not have this RTP packet available to re-send, it just ignores the message.

Sender and Receiver Reports #

These reports are used to send statistics between agents. This communicates the amount of packets actually received and jitter.

The reports can be used for diagnostics and congestion control.

How RTP/RTCP solve problems together #

RTP and RTCP then work together to solve all the problems caused by networks. These techniques are still constantly changing!

Forward Error Correction #

Also known as FEC. Another method of dealing with packet loss. FEC is when you send the same data multiple times, without it even being requested. This is done at the RTP level, or even lower with the codec.

If the packet loss for a call is steady then FEC is a much lower latency solution than NACK. The round trip time of having to request, and then re-transmit the missing packet can be significant for NACKs.

Adaptive Bitrate and Bandwidth Estimation #

As discussed in the Real-time networking chapter, networks are unpredictable and unreliable. Bandwidth availability can change multiple times throughout a session. It is not uncommon to see available bandwidth change dramatically (orders of magnitude) within a second.

The main idea is to adjust encoding bitrate based on predicted, current, and future available network bandwidth. This ensures that video and audio signal of the best possible quality is transmitted, and the connection does not get dropped because of network congestion. Heuristics that model the network behavior and tries to predict it is known as Bandwidth estimation.

There is a lot of nuance to this, so let’s explore in greater detail.

Identifying and Communicating Network Status #

RTP/RTCP runs over all types of different networks, and as a result, it’s common for some communication to be dropped on its way from the sender to the receiver. Being built on top of UDP, there is no built-in mechanism for packet retransmission, let alone handling congestion control.

To provide users the best experience, WebRTC must estimate qualities about the network path, and adapt to how those qualities change over time. The key traits to monitor include: available bandwidth (in each direction, as it may not be symmetric), round trip time, and jitter (fluctuations in round trip time). It needs to account for packet loss, and communicate changes in these properties as network conditions evolve.

There are two primary objectives for these protocols:

- Estimate the available bandwidth (in each direction) supported by the network.

- Communicate network characteristics between sender and receiver.

RTP/RTCP has three different approaches to address this problem. They all have their pros and cons, and generally each generation has improved over its predecessors. Which implementation you use will depend primarily on the software stack available to your clients and the libraries available for building your application.

Receiver Reports / Sender Reports #

The first implementation is the pair of Receiver Reports and its complement, Sender Reports. These RTCP messages are defined in RFC 3550, and are responsible for communicating network status between endpoints. Receiver Reports focuses on communicating qualities about the network (including packet loss, round-trip time, and jitter), and it pairs with other algorithms that are then responsible for estimating available bandwidth based on these reports.

Sender and Receiver reports (SR and RR) together paint a picture of the network quality. They are sent on a schedule for each SSRC, and they are the inputs used when estimating available bandwidth. Those estimates are made by the sender after receiving the RR data, containing the following fields:

- Fraction Lost - What percentage of packets have been lost since the last Receiver Report.

- Cumulative Number of Packets Lost - How many packets have been lost during the entire call.

- Extended Highest Sequence Number Received - What was the last Sequence Number received, and how many times has it rolled over.

- Interarrival Jitter - The rolling Jitter for the entire call.

- Last Sender Report Timestamp - Last known time on sender, used for round-trip time calculation.

SR and RR work together to compute round-trip time.

The sender includes its local time, sendertime1 in SR. When the receiver gets an SR packet, it

sends back RR. Among other things, the RR includes sendertime1 just received from the sender.

There will be a delay between receiving the SR and sending the RR. Because of that, the RR also

includes a “delay since last sender report” time - DLSR. The DLSR is used to adjust the

round-trip time estimate later on in the process. Once the sender receives the RR it subtracts

sendertime1 and DLSR from the current time sendertime2. This time delta is called round-trip

propagation delay or round-trip time.

rtt = sendertime2 - sendertime1 - DLSR

Round-trip time in plain English:

- I send you a message with my clock’s current reading, say it is 4:20pm, 42 seconds and 420 milliseconds.

- You send me this same timestamp back.

- You also include the time elapsed from reading my message to sending the message back, say 5 milliseconds.

- Once I receive the time back, I look at the clock again.

- Now my clock says 4:20pm, 42 seconds 690 milliseconds.

- It means that it took 265 milliseconds (690 - 420 - 5) to reach you and return back to me.

- Therefore, the round-trip time is 265 milliseconds.

TMMBR, TMMBN, REMB and TWCC, paired with GCC #

Google Congestion Control (GCC) #

The Google Congestion Control (GCC) algorithm (outlined in draft-ietf-rmcat-gcc-02) addresses the challenge of bandwidth estimation. It pairs with a variety of other protocols to facilitate the associated communication requirements. Consequently, it is well-suited to run on either the receiving side (when run with TMMBR/TMMBN or REMB) or on the sending side (when run with TWCC).

To arrive at estimates for available bandwidth, GCC focuses on packet loss and fluctuations in frame arrival time as its two primary metrics. It runs these metrics through two linked controllers: the loss-based controller and the delay-based controller.

GCC’s first component, the loss-based controller, is simple:

- If packet loss is above 10%, the bandwidth estimate is reduced.

- If packet loss is between 2-10%, the bandwidth estimate stays the same.

- If packet loss is below 2%, the bandwidth estimate is increased.

Packet loss measurements are taken frequently. Depending on the paired communication protocol, packet loss may either be explicitly communicated (as with TWCC) or inferred (as with TMMBR/TMMBN and REMB). These percentages are evaluated over time windows of around one second.

The delay-based controller cooperates with the loss-based controller, and looks at the variations in packet arrival time. This delay-based controller aims to identify when network links are becoming increasingly congested, and may reduce bandwidth estimates even before packet loss occurs. The theory is that the busiest network interface along the path will continue queuing up packets until the interface runs out of capacity inside its buffers. If that interface continues to receive more traffic than it is able to send, it will be forced to drop all packets that it cannot fit into its buffer space. This type of packet loss is particularly disruptive for low-latency/real-time communication, but it can also degrade throughput for all communication over that link and should ideally be avoided. Thus, GCC tries to figure out if network links are growing larger and larger queue depths before packet loss actually occurs. It will reduce the bandwidth usage if it observes increased queuing delays over time.

To achieve this, GCC tries to infer increases in queue depth by measuring subtle increases in round

trip time. It records frames’ “inter-arrival time”, t(i) - t(i-1): the difference in arrival time

of two groups of packets (generally, consecutive video frames). These packet groups frequently

depart at regular time intervals (e.g. every 1/24 seconds for a 24 fps video). As a result,

measuring inter-arrival time is then as simple as recording the time difference between the start of

the first packet group (i.e. frame) and the first frame of the next.

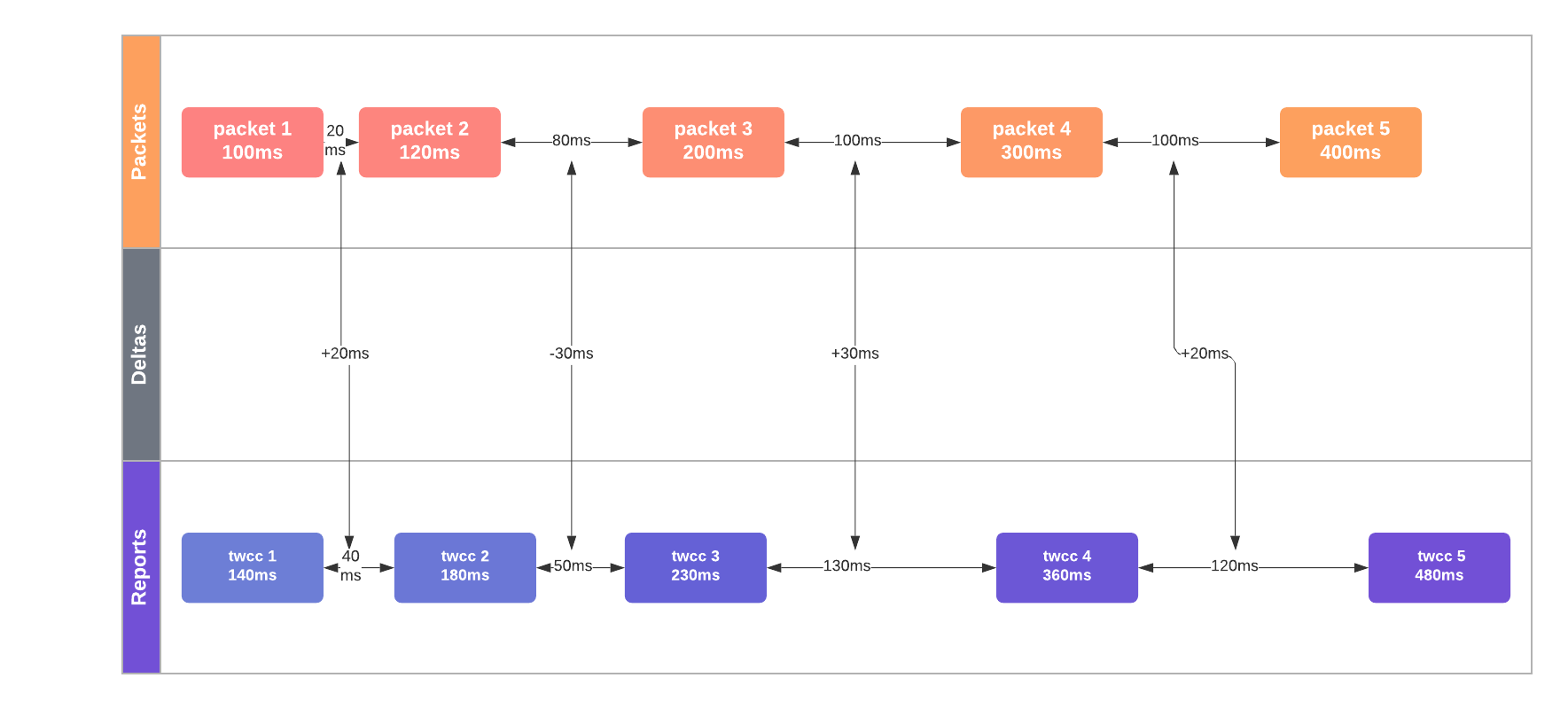

In the diagram below, the median inter-packet delay increase is +20 msec, a clear indicator of network congestion.

If inter-arrival time increases over time, that is presumed evidence of increased queue depth on connecting network interfaces and considered to be network congestion. (Note: GCC is smart enough to control these measurements for fluctuations in frame byte sizes.) GCC refines its latency measurements using a Kalman filter and takes many measurements of network round-trip times (and its variations) before flagging congestion. One can think of GCC’s Kalman filter as taking the place of a linear regression: helping to make accurate predictions even when jitter adds noise into the timing measurements. Upon flagging congestion, GCC will reduce the available bitrate. Alternatively, under steady network conditions, it can slowly increase its bandwidth estimates to test out higher load values.

TMMBR, TMMBN, and REMB #

For TMMBR/TMMBN and REMB, the receiving side first estimates available inbound bandwidth (using a protocol such as GCC), and then communicates these bandwidth estimates to the remote senders. They do not need to exchange details about packet loss or other qualities about network congestion because operating on the receiving side allows them to measure inter-arrival time and packet loss directly. Instead, TMMBR, TMMBN, and REMB exchange just the bandwidth estimates themselves:

- Temporary Maximum Media Stream Bit Rate Request - A mantissa/exponent of a requested bitrate for a single SSRC.

- Temporary Maximum Media Stream Bit Rate Notification - A message to notify that a TMMBR has been received.

- Receiver Estimated Maximum Bitrate - A mantissa/exponent of a requested bitrate for the entire session.

TMMBR and TMMBN came first and are defined in RFC 5104. REMB came later, there was a draft submitted in draft-alvestrand-rmcat-remb, but it was never standardized.

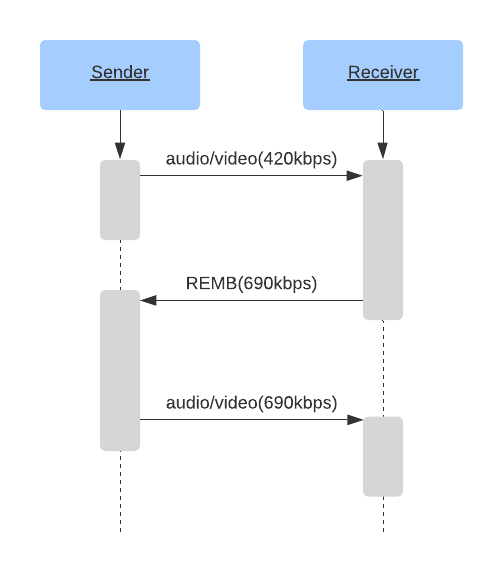

An example session that uses REMB might behave like the following:

This method works great on paper. The Sender receives estimation from the receiver, sets encoder bitrate to the received value. Tada! We’ve adjusted to the network conditions.

However in practice, the REMB approach has multiple drawbacks.

Encoder inefficiency is the first. When you set a bitrate for the encoder, it won’t necessarily output the exact bitrate you requested. Encoding may output more or fewer bits, depending on the encoder settings and the frame being encoded.

For example, using the x264 encoder with tune=zerolatency can significantly deviate from the specified target bitrate. Here is a possible scenario:

- Let’s say we start off by setting the bitrate to 1000 kbps.

- The encoder outputs only 700 kbps, because there is not enough high frequency features to encode. (AKA - “staring at a wall”.)

- Let’s also imagine that the receiver gets the 700 kbps video at zero packet loss. It then applies REMB rule 1 to increase the incoming bitrate by 8%.

- The receiver sends a REMB packet with a 756 kbps suggestion (700 kbps * 1.08) to the sender.

- The sender sets the encoder bitrate to 756 kbps.

- The encoder outputs an even lower bitrate.

- This process continues to repeat itself, lowering the bitrate to the absolute minimum.

You can see how this would cause heavy encoder parameter tuning, and surprise users with unwatchable video even on a great connection.

Transport Wide Congestion Control #

Transport Wide Congestion Control is the latest development in RTCP network status communication. It is defined in draft-holmer-rmcat-transport-wide-cc-extensions-01, but has also never been standardized.

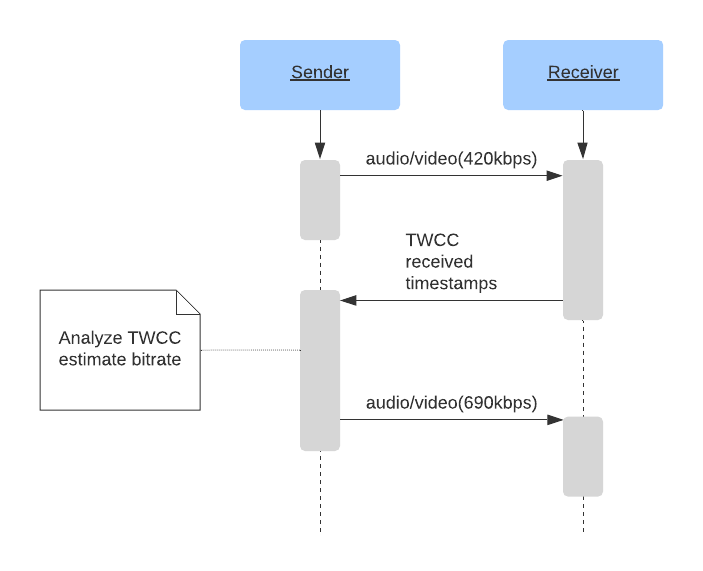

TWCC uses a quite simple principle:

With REMB, the receiver instructs the sending side in the available download bitrate. It uses precise measurements about inferred packet loss and data only it has about inter-packet arrival time.

TWCC is almost a hybrid approach between the SR/RR and REMB generations of protocols. It brings the bandwidth estimates back to the sender side (similar to SR/RR), but its bandwidth estimate technique more closely resembles the REMB generation.

With TWCC, the receiver lets the sender know the arrival time of each packet. This is enough information for the sender to measure inter-packet arrival delay variation, as well as identifying which packets were dropped or arrived too late to contribute to the audio/video feed. With this data being exchanged frequently, the sender able to quickly adjust to changing network conditions and vary its output bandwidth using an algorithm such GCC.

The sender keeps track of sent packets, their sequence numbers, sizes and timestamps. When the sender receives RTCP messages from the receiver, it compares the send inter-packet delays with the receive delays. If the receive delays increase, it signals network congestion, and the sender must take corrective measures.

By providing the sender with the raw data, TWCC provides an excellent view into real time network conditions:

- Almost instant packet loss behavior, down to the individual lost packets

- Accurate send bitrate

- Accurate receive bitrate

- Jitter measurement

- Differences between send and receive packet delays

- Description of how the network tolerated bursty or steady bandwidth delivery

One of the most significant contributions of TWCC is the flexibility it affords to WebRTC developers. By consolidating the congestion control algorithm to the sending side, it allows simple client code that can be widely used and requires minimal enhancements over time. The complex congestion control algorithms can then be iterated more quickly on the hardware they directly control (like the Selective Forwarding Unit, discussed in section 8). In the case of browsers and mobile devices, this means those clients can benefit from algorithm enhancements without having to await standardization or browser updates (which can take quite a long time to be widely available).

Bandwidth Estimation Alternatives #

The most deployed implementation is “A Google Congestion Control Algorithm for Real-Time Communication” defined in draft-alvestrand-rmcat-congestion.

There are several alternatives to GCC, for example NADA: A Unified Congestion Control Scheme for Real-Time Media and SCReAM - Self-Clocked Rate Adaptation for Multimedia.