What, Why and How #

What is WebRTC? #

WebRTC, short for Web Real-Time Communication, is both an API and a Protocol. The WebRTC protocol is a set of rules for two WebRTC agents to negotiate bi-directional secure real-time communication. The WebRTC API then allows developers to use the WebRTC protocol. The WebRTC API is specified only for JavaScript.

A similar relationship would be the one between HTTP and the Fetch API. The WebRTC protocol would be HTTP, and the WebRTC API would be the Fetch API.

The WebRTC protocol is available in other APIs and languages besides JavaScript. You can find servers and domain-specific tools as well for WebRTC. All of these implementations use the WebRTC protocol so that they can interact with each other.

The WebRTC protocol is maintained in the IETF in the rtcweb working group. The WebRTC API is documented in the W3C as webrtc.

Why should I learn WebRTC? #

These are some of the things that WebRTC will give you:

- Open standard

- Multiple implementations

- Available in browsers

- Mandatory encryption

- NAT Traversal

- Repurposed existing technology

- Congestion control

- Sub-second latency

This list is not exhaustive, just an example of some of the things you may appreciate during your journey. Don’t worry if you don’t know all these terms yet, this book will teach them to you along the way.

The WebRTC Protocol is a collection of other technologies #

The WebRTC Protocol is an immense topic that would take an entire book to explain. However, to start off we break it into four steps.

- Signaling

- Connecting

- Securing

- Communicating

These steps are sequential, which means the prior step must be 100% successful for the subsequent step to begin.

One peculiar fact about WebRTC is that each step is actually made up of many other protocols! To make WebRTC, we stitch together many existing technologies. In that sense, you can think of WebRTC as being more a combination and configuration of well-understood tech dating back to the early 2000s than as a brand-new process in its own right.

Each of these steps has dedicated chapters, but it is helpful to understand them at a high level first. Since they depend on each other, it will help when explaining further the purpose of each of these steps.

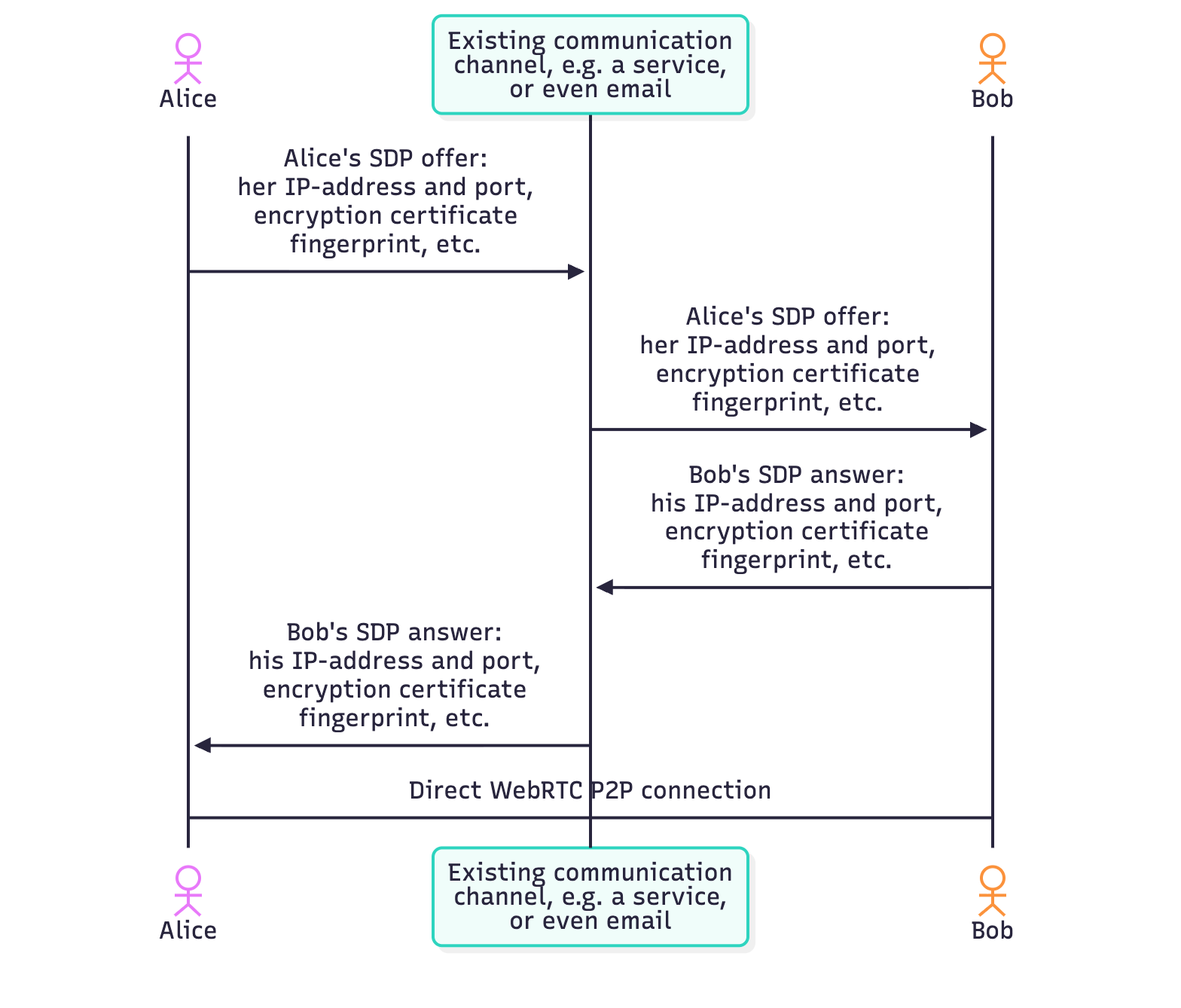

Signaling: How peers find each other in WebRTC #

When a WebRTC Agent starts, it has no idea who it is going to communicate with or what they are going to communicate about. The Signaling step solves this issue! Signaling is used to bootstrap the call, allowing two independent WebRTC agents to start communicating.

Signaling uses an existing, plain-text protocol called SDP (Session Description Protocol). Each SDP message is made up of key/value pairs and contains a list of “media sections”. The SDP that the two WebRTC agents exchange contains details like:

- The IPs and Ports that the agent is reachable on (candidates).

- The number of audio and video tracks the agent wishes to send.

- The audio and video codecs each agent supports.

- The values used while connecting (

uFrag/uPwd). - The values used while securing (certificate fingerprint).

It is very important to note that signaling typically happens “out-of-band”, which means applications generally don’t use WebRTC itself to exchange signaling messages. There needs to be another communication channel between the two parties before they can initiate a WebRTC connection. The kind of channel being used is not a concern of WebRTC. Any architecture suitable for sending messages can relay the SDPs between the connecting peers, and many applications will simply use their existing infrastructure (e.g. REST endpoints, WebSocket connections, or authentication proxies) to facilitate trading of SDPs between the proper clients.

Connecting and NAT Traversal with STUN/TURN #

Once two WebRTC agents have exchanged SDPs, they have enough information to attempt to connect to each other. To make this connection happen, WebRTC uses another established technology called ICE (Interactive Connectivity Establishment).

ICE is a protocol that pre-dates WebRTC and allows the establishment of a direct connection between two agents without a central server. These two agents could be on the same network or on the other side of the world.

ICE enables direct connection, but the real magic of the connecting process involves a concept called ‘NAT Traversal’ and the use of STUN/TURN Servers. These two concepts, which we will explore in more depth later, are all you need to communicate with an ICE Agent in another subnet.

When the two agents have successfully established an ICE connection, WebRTC moves on to the next step; establishing an encrypted transport for sharing audio, video, and data between them.

Securing the transport layer with DTLS and SRTP #

Now that we have bi-directional communication (via ICE), we need to make our communication secure! This is done through two more protocols that also pre-date WebRTC; DTLS (Datagram Transport Layer Security) and SRTP (Secure Real-Time Transport Protocol). The first protocol, DTLS, is simply TLS over UDP (TLS is the cryptographic protocol used to secure communication over HTTPS). The second protocol, SRTP, is used to ensure encryption of RTP (Real-time Transport Protocol) data packets.

First, WebRTC connects by doing a DTLS handshake over the connection established by ICE. Unlike HTTPS, WebRTC doesn’t use a central authority for certificates. It simply asserts that the certificate exchanged via DTLS matches the fingerprint shared via signaling. This DTLS connection is then used for DataChannel messages.

Next, WebRTC uses the RTP protocol, secured using SRTP, for audio/video transmission. We initialize our SRTP session by extracting the keys from the negotiated DTLS session.

We will discuss why media and data transmission have their own protocols in a later chapter, but for now it is enough to know that they are handled separately.

Now we are done! We have successfully established bi-directional and secure communication. If you have a stable connection between your WebRTC agents, this is all the complexity you need. In the next section, we will discuss how WebRTC deals with the unfortunate real world problems of packet loss and bandwidth limits.

Communicating with peers via RTP and SCTP #

Now that we have two WebRTC agents connected and secure, bi-directional communication established, let’s start communicating! Again, WebRTC will use two pre-existing protocols: RTP (Real-time Transport Protocol), and SCTP (Stream Control Transmission Protocol). We use RTP to exchange media encrypted with SRTP, and we use SCTP to send and receive DataChannel messages encrypted with DTLS.

RTP is quite a minimal protocol, but it provides the necessary tools to implement real-time streaming. The most important thing about RTP is that it gives flexibility to the developer, allowing them to handle latency, package loss, and congestion as they please. We will discuss this further in the media chapter.

The final protocol in the stack is SCTP. The important thing about SCTP is that you can turn off reliable and in order message delivery (among many different options). This allows developers to ensure the necessary latency for real-time systems.

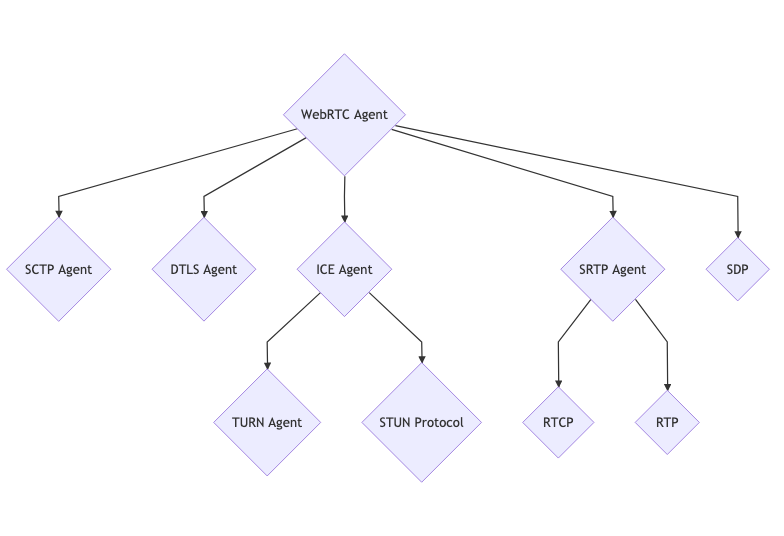

WebRTC, a collection of protocols #

WebRTC solves a lot of problems. At first glance the technology may seem over-engineered, but the genius of WebRTC is its humility. It wasn’t created under the assumption that it could solve everything better. Instead, it embraced many existing single purpose technologies and brought them together into a streamlined, widely applicable bundle.

This allows us to examine and learn each part individually without being overwhelmed. A good way to visualize it is a ‘WebRTC Agent’ is really just an orchestrator of many different protocols.

How does the WebRTC API work? #

This section outlines how the WebRTC JavaScript API maps to the WebRTC protocol described above. It isn’t meant as an extensive demo of the WebRTC API, but more to create a mental model of how everything ties together. If you aren’t familiar with either the protocol or the API, don’t worry. This could be a fun section to return to as you learn more!

new RTCPeerConnection

#

The RTCPeerConnection is the top-level “WebRTC Session”. It contains all the protocols mentioned above. The subsystems are all allocated but nothing happens yet.

addTrack

#

addTrack creates a new RTP stream. A random Synchronization Source (SSRC) will be generated for this stream. This stream will then be inside the Session Description generated by createOffer inside a media section. Each call to addTrack will create a new SSRC and media section.

Immediately after an SRTP Session is established, these media packets will start being encrypted using SRTP and sent via ICE.

createDataChannel

#

createDataChannel creates a new SCTP stream if no SCTP association exists. SCTP is not enabled by default. It is only started when one side requests a data channel.

Immediately after a DTLS Session is established, the SCTP association will start sending packets encrypted with DTLS via ICE.

createOffer

#

createOffer generates a Session Description of the local state to be shared with the remote peer.

The act of calling createOffer doesn’t change anything for the local peer.

setLocalDescription

#

setLocalDescription commits any requested changes. The calls addTrack, createDataChannel, and similar calls are temporary until this call. setLocalDescription is called with the value generated by createOffer.

Usually, after this call, you will send the offer to the remote peer, who will use it to call setRemoteDescription.

setRemoteDescription

#

setRemoteDescription is how we inform the local agent about the state of the remote candidates. This is how the act of ‘Signaling’ is done with the JavaScript API.

When setRemoteDescription has been called on both sides, the WebRTC agents now have enough info to start communicating Peer-To-Peer (P2P)!

addIceCandidate

#

addIceCandidate allows a WebRTC agent to add more remote ICE Candidates at any time. This API sends the ICE Candidate right into the ICE subsystem and has no other effect on the greater WebRTC connection.

ontrack

#

ontrack is a callback fired when an RTP packet is received from the remote peer. The incoming packets would have been declared in the Session Description that was passed to setRemoteDescription.

WebRTC uses the SSRC and looks up the associated MediaStream and MediaStreamTrack, and fires this callback with these details populated.

oniceconnectionstatechange

#

oniceconnectionstatechange is a callback that is fired which reflects a change in the state of an ICE agent. When you have a change in network connectivity this is how you are notified.

onconnectionstatechange

#

onconnectionstatechange is a combination of ICE agent and DTLS agent state. You can watch this to be notified when ICE and DTLS have both completed successfully.